▸ virtual environments

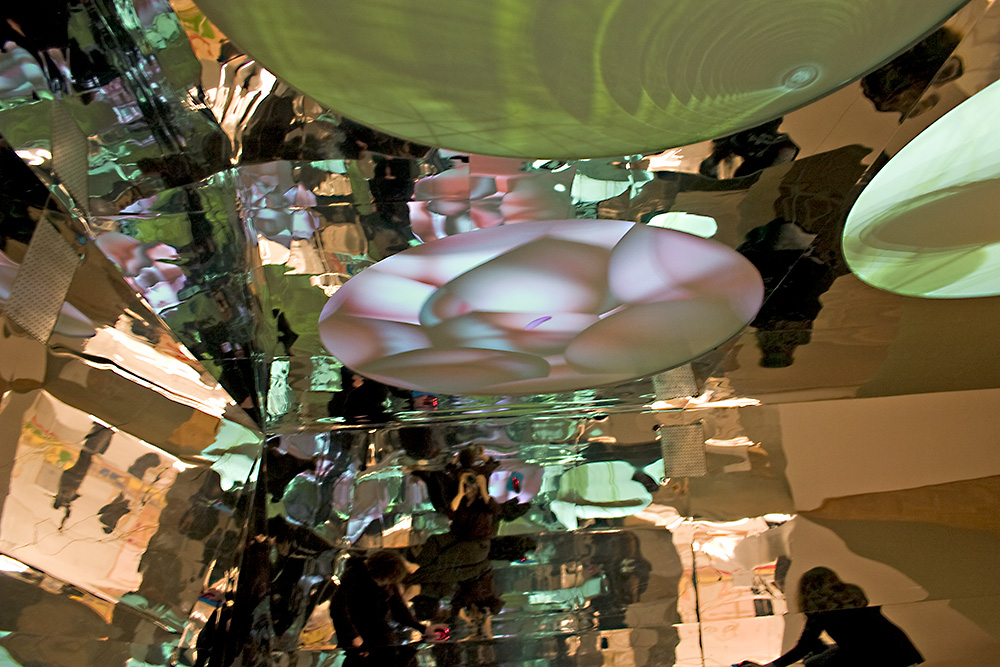

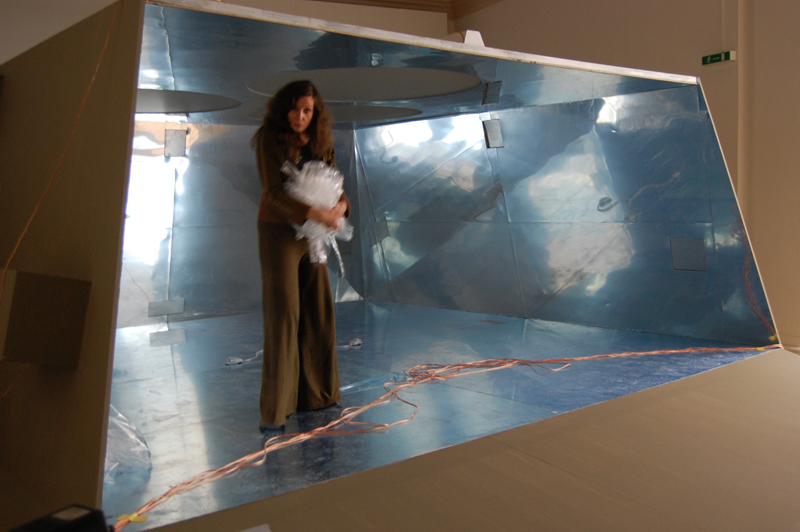

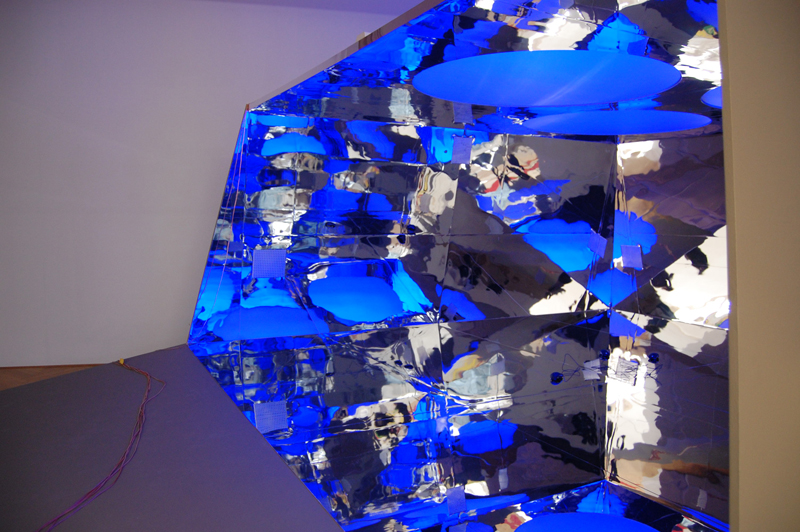

Mirror Cells / Spiegelzellen, 2007, installation view

Mirror Cells | Spiegelzellen

Accessible immersive environment.

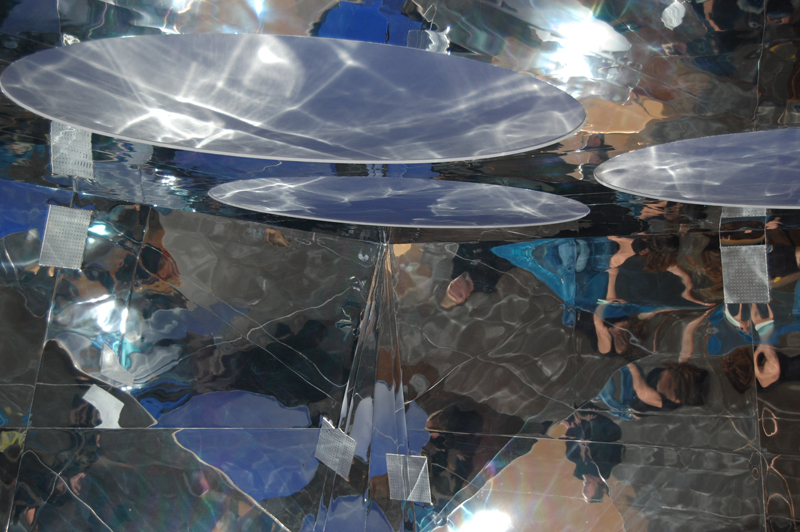

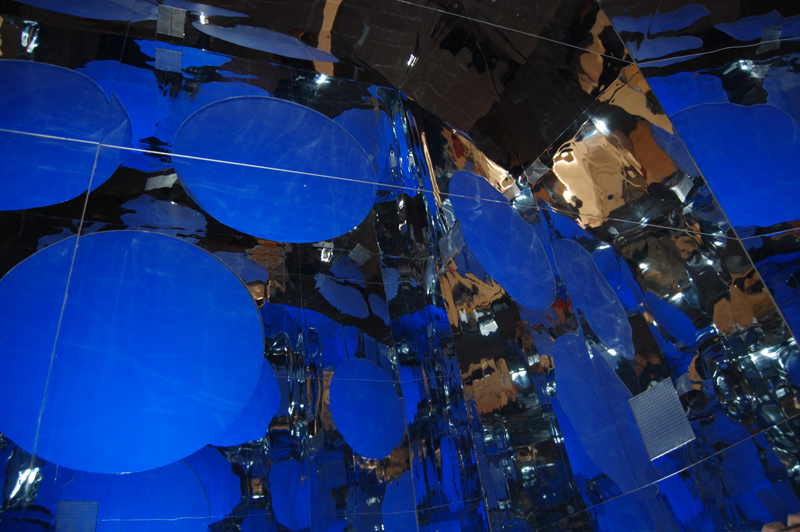

Infinitely mirrored acousmatic-visual 3D-world.

Sylvia Eckermann’s Audio-visual Installation Mirror Cells: The Exploration and Collaboration of Viewers in a Game Mod

The question of an artwork’s relative importance was first radically posed in the mid 1950s. And since the issue of actively involving the audience seemed to become the counter movement to the hitherto “artist-work-viewer” constellation, the historical avant-garde—in the sense of Peter Bürger1—can be seen as the essential starting point for the increasingly more active and performing role of the recipient in a haptically accessible installation. In it, it is the viewer who applies the finishing touches to a work of art, and by bringing it to some sort of completion, conclusion or (if you like) perfection, his or her activity has a decisive effect. The recipients’ involvement was strengthened while their participation was and still is supposed to grant the viewer a fundamental role in the work of art.

Ideologically speaking, this movement, if we were to categorize participatory art or even interactive media art, begins when the artist decides to take leave of a modernistic understanding of a work’s self-sufficient status. The object functions only partially as object; in order to be understood and then changed accordingly, it needs and calls for an active participant. One could say the work does not yet exist one hundred percent because it still depends on the viewer in order to be (effectively) finished. The artwork has to some extent liberated itself from its “egotism” and by being transformed it generates a strong object in terms of the various meanings generated by the participants and added to the already existing ones.

This also applies to Sylvia Eckermann’s Spiegelzellen (Mirror Cells, 2007), a sound, image, and room installation of computer controlled rhizome structures she created in collaboration with Szely and Doron Goldfarb. Sylvia Eckermann’s work with multi-user applications and the interface between virtual and haptically accessible space goes back to 1989 when she first started exploring electronic art and created complex multi-media worlds involving the viewers in a number of ways and enabling them to act and experiment both in reality and in virtual space. In the words of Sylvia Eckermann, the audio-visual room installations allow the viewers to become actors.

For the exhibition “Acting in Utopia” at Landesgalerie Linz in 2007, Eckermann, Szely (sound) and Goldfarb (programming) developed an architectural acousmatic space, a world of reflective mirror plates which tempted the viewers to be led into the unknown. Visitors to the museum were invited to play “a game of reflected infinity”2 in which with the help of a mouse they could pass through the sound and image environment and thus actively travel the virtual world. The project is based on the phenomenon of mirror neurons or mirror cells discovered in 1991 by Giacomo Rizzolatti and a group of neurophysiologists at the University of Parma. In the process of observing someone else’s activities, these mirror neurons trigger in the brain of the observer exactly the same potentials as if they were carrying out the activities themselves3. In the particular “organism” of Spiegelzellen, recipients of the work are faced with quite a challenge. They are given the opportunity to potentially initiate the digital work within the environment, control it and also manipulate it where appropriate. For the “mirror” structure as such to ultimately function, the players have to communicate in the game mod in order to create the environment’s highly different variables in terms of form, sound and the dynamics of the sound architectural structure. In her text about Spiegelzellen and the game played by the participants in the interactive media installation, Sylvia Eckermann gives the following description: “I, my ego mirrored into infinity, my acousmatic ego, the ego which can explore the electronic space, i.e., my simulated ego, creates images, colors and sounds—the we, the collective, creates rooms and harmonies, architectural shapes and compositions. Time will eventually disintegrate everything thereby making room for something new to emerge.”4 The artist points out the temporary nature of the interaction and links it to a virtual knowledge space set up by the artists. The process, i.e., the path to this virtual world, is also revealed as productive and creative one. The viewers’ creativity emerges in “the perception of one’s own cognition and the communication with oneself and others as a mirror image of those recently discovered mirror cells that presumably offer a convincing explanation of concepts such as empathy, learning, the development of language and culture and as such seem to be fundamentally responsible for human social behavior.”5

The social correlations immanent in the art work result both from the openness of the physical construction and from sitting together on the floor of the installation. Thus, the experience and the perception include a physical aspect as well. According to Maurice Merleau-Ponty, the executions and respective activities carried out in an installation are effectively experienced inside the viewers’ body. Hence, he looks at their positioning and the importance of their body within the room, which in turn allows for examining and analyzing the movement and the perception of the body inside the room in a phenomenological light.

The world is experienced by the body and the body is understood as the “subject’s most immediate object”.6 The perception and observation of other objects first pass through the body and not our conscious awareness. The prerequisite for this peripatetic experience, which the viewer will make upon entering these rooms, is naturally physical. So, prior to experiencing the space peripatetically, the viewer explores it with his or her senses. According to Merleau-Ponty, each and every access to the world takes place through the senses. Consequently the perception of things is fundamental for our sense of motion and our orientation in a world which is full of sensations such as sounds, smells, haptic forms, and visual aspects in the sense of colors.8

From this perspective, the player’s potential is indeed great and the actions open to the individual allow, in the words of Merleau-Ponty, for an opening to the world. In Spiegelzellen, this new world can be understood as the virtual space that allows for new possibilities of experience.7 The physical aspect is enriched by a communicative and social level, which in turn opens up a new perspective for the viewer.

These possibilities are observed by the other players and the result is a collective togetherness as opposed to one against the other, as so often seems to be the aim in the digital world. In Spiegelzellen, Eckermann, Szely and Goldfarb integrated another participative element: By asking visitors to send them text messages which were then integrated in the 3D world the artists created yet another communication tool between the real world and the mirror world.

Acting and communicating in the virtual world can be seen as part of a process in a constant state of flux. Communicating and the creative process per se are thereby elevated to a work of art in its own right.

The communicative as an (art) object refers to a different formal level since communication is not physically palpable. But here, too, it is possible to speak of an extension of the artwork since the participation and thus the role of the viewer in Spiegelzellen represents a second level on which a new work was produced, one which is, however, not comprehensible as a real and palpable object.

It is important to point out that the traditional work of art and the act of the viewer—be it on a physical or on a communicative level—belong together and are symbiotically dependent on each other. In Eckermann’s Spiegelzellen this would be the relationship between the installation, the actors, the communication and the creative activity in the digital world. Together they create a new level and a second object that could be called a transformed or extended object, or more precisely an object-object. It is not, as with Peter Weibel, an open field of action but the next level which addresses an object not entirely comprehensible.

The result of the participatory work of art could therefore be labeled with the term artwork210 because the active involvement of the participants has a decisive effect; it represents an executing, active intervention and is reflected precisely in the final effect of the work and its result. Thus, what remains with the active viewers is both the communication as well as their considerations and reflections which developed by means of the active process.

- See Peter Bürger, Theorie der Avantgarde (Frankfurt am Main, 1974).

- Dieter Buchhart 2007, unpublished material

- Ibid

- Sylvia Eckermann 2007.

- Ibid

- Ole Fogh Kirkeby, “Introduktion,” in: Merleau-Ponty, Kroppens fænomenologi (Frederiksberg, 2000), p. xi.

- We speak of a peripatetic observation in connection with an understanding and registration of the entirety of a spatial structure if it is crossed and experienced by a viewer. See Ernst-Gerhard Güse, Richard Serra (Stuttgart, 1987), p. 45.

- See Arne Grøn, “Merleau-Ponty: Sansning og verden,” in: Vor tids filosofi. Engagement og forståelse, ed. Paul Lübcke (Copenhagen, 1996), p. 332.

- See Peter Weibel, “Kunst als offenes Handlungsfeld,” in: Offene Handlungsfelder, ed. Peter Weibel (Cologne, 1999).

- See Anna Karina Hofbauer, Die Öffnung und die Erweiterung des Kunstbegriffs durch partizipative und interaktive Werke vor dem Hintergrund und der Analyse der physischen Beteiligung des Betrachters/der Betrachterin von der historischen Avantgarde bis zur zeitgenössischen Kunst, Ph.D. thesis, Kunstuniversität Linz, 2013, pp. 292–302.

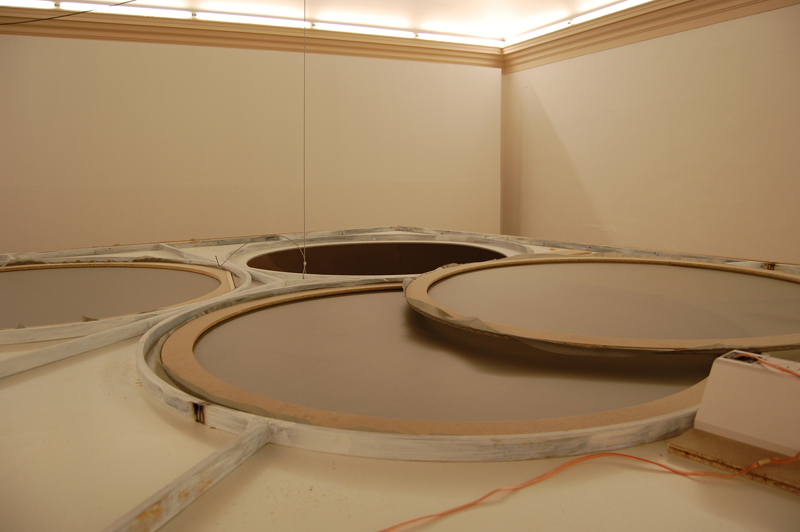

Mirror Cells, 2007, layout.

3 circular projection screens, 3 projectors,

8 speakers,

mirrored interior,

wooden construction, 1000 x 500 x 500 cm.

CREDITS: Idea, Concept, Architecture, GameArt: Sylvia Eckermann, Acousmatic Space, Composition: Peter Szely, Programming, Unrealscripting: Doron Goldfarb, Additional Credits: Christoph Staber, Gernot Dannereder: Player Model and Animation.

Mirror Cells was a feature-project of ars electronica 2007

and was seen at the exhibition: Acting in Utopia Sep 5 - Nov 11 2007 Landesgalerie Linz AT,

curated by: Anna Karina Hofbauer & Dieter Buchhart.

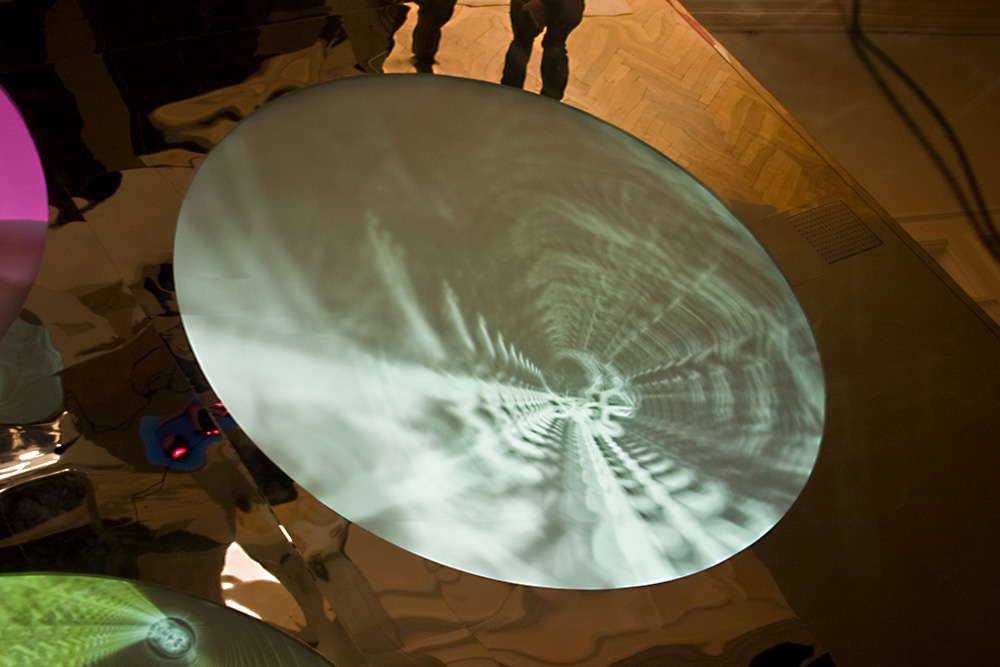

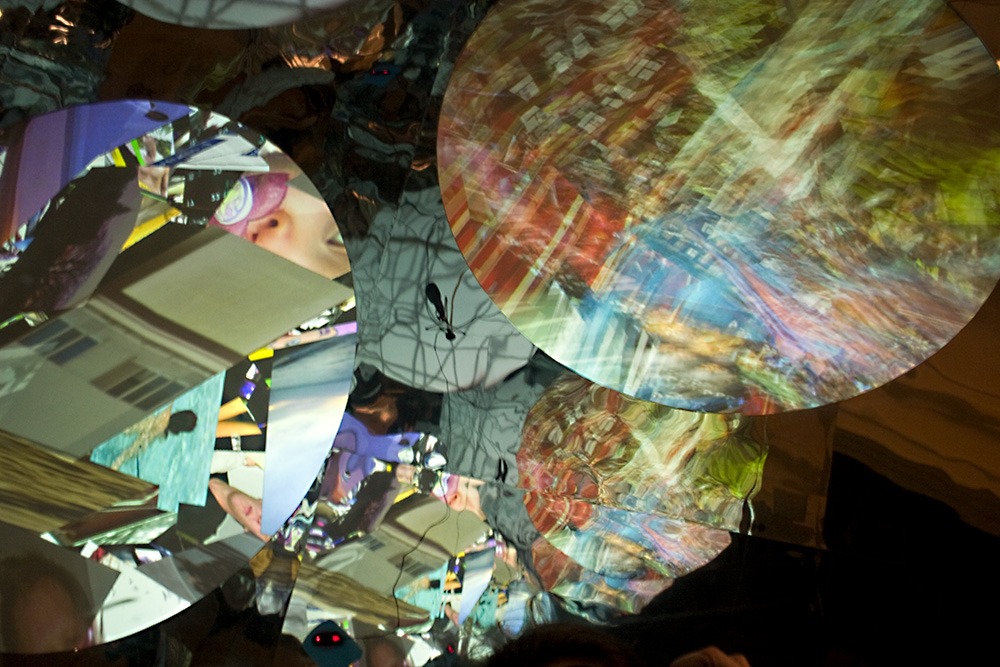

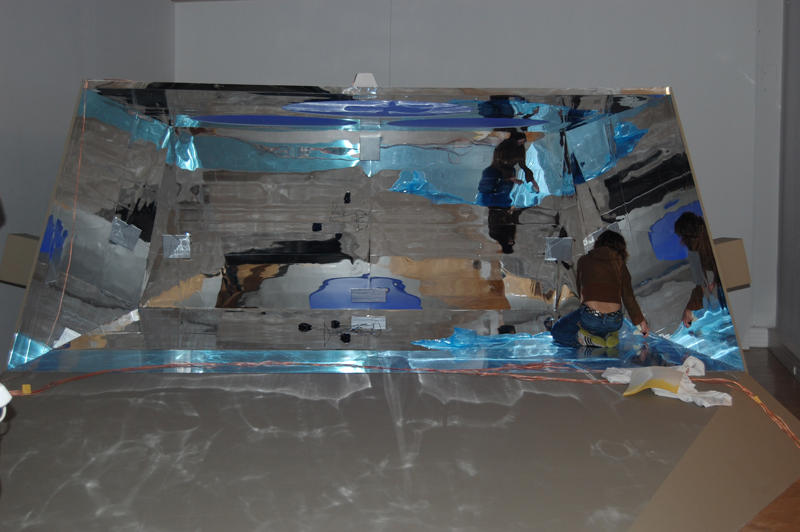

Mirror Cells / Spiegelzellen, 2007, installation view, photos: Gerda Leopold.

Mirror Cells / Spiegelzellen, 2007, construction.