naked eye

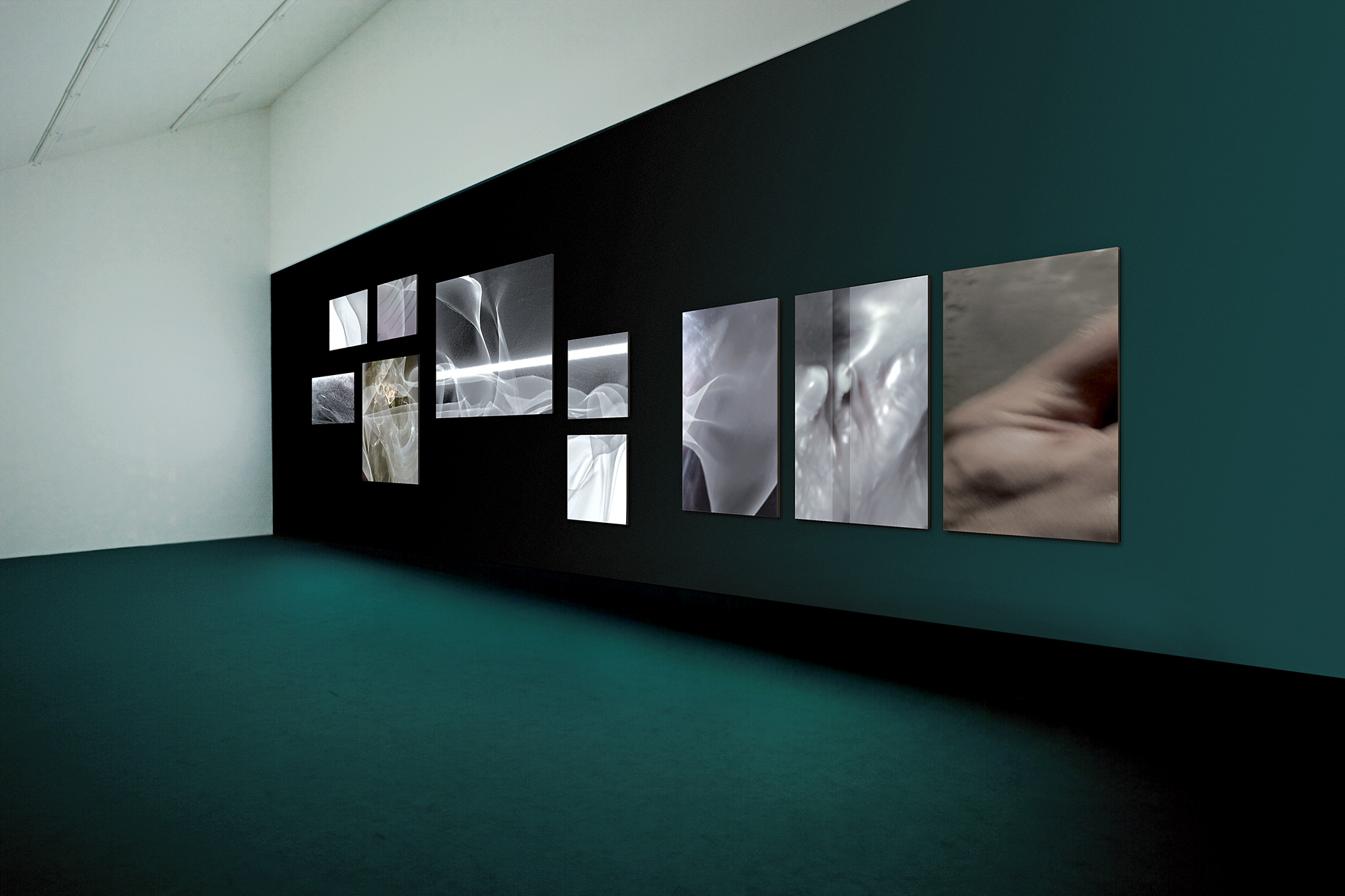

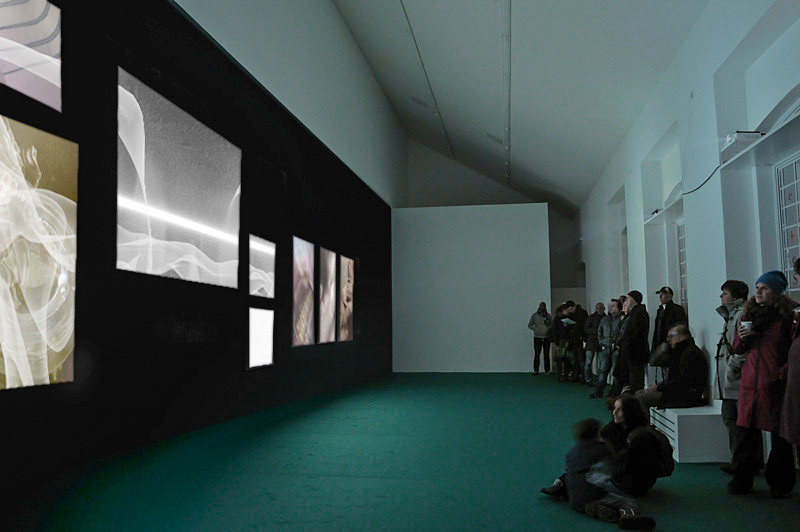

installation, 3 channel video, 5.1 sound by Szely, 1500 x 470 cm. 10 projection objects, carpet, text work plotted on mirror foils.

Solo exhibition at kunstraum BERNSTEINER, Vienna, 12/1 2010 - 22/01 2011

Brigitte Felderer

Intangible Images

With her installation naked eye at Kunstraum Bernsteiner Sylvia Eckermann addresses the presentation of the "white cube" by subverting the boundaries between tableaux vivants and animated images, between the flat wall and a visual depth, between the visible and the audible space. The viewer is immersed into a space of vexed imagination that constantly changes its content, and disintegrates any type of narration and sensually reflects the familiar presentations of art and its many media.

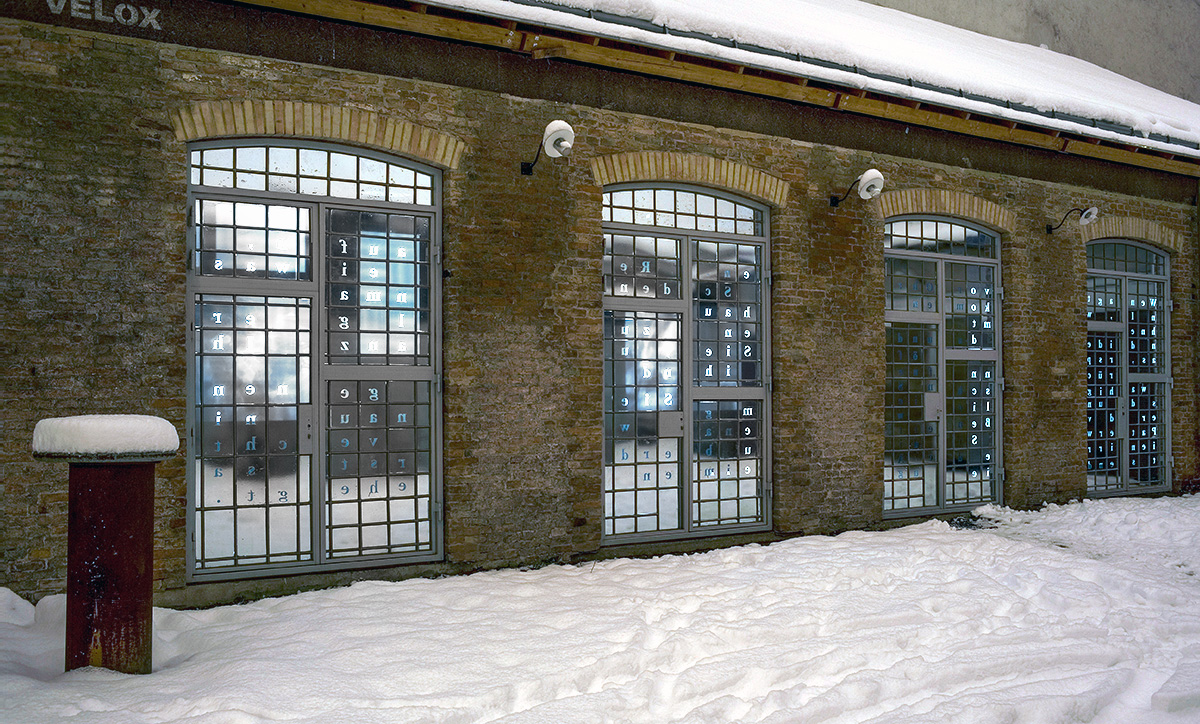

Kunstraum Bernsteiner is entered through a large apartment building, leading to an inner courtyard. Located to one side of the courtyard there are large windows belonging to a former workshop. The previous manufacturing site was turned into a gallery space several years ago, today it is full of light, wide and white. With Sylvia Eckermann's intervention at the Kunstraum, not a lot was changed but basically nothing remained the same.

On entering the space you are confronted with a long wall painted in the same dark green as the installed carpet covering the entire floor. The view to the outside – through the large windows – is reflected back inside by mirror foil. Although in bright daylight these mirrors become transparent, they retain their silvery colour thus lending the patina of an old film to the outside reality and making it appear like a projection. The view of the courtyard becomes an extension of the gallery, a continuation, resulting in the barrier blurring the lines between inside and outside. In the gallery the changing daylight becomes part of this experience; the natural light fluctuations seems to follow a specific concept set by the artist.

The room's original dimensions are no longer discernible. The wall – long and reminicant of exhibition rooms common in 19th century – is pulled in like a prop. In the installation, this large green wall is hung with paintings, neither arranged according to a particular period or content, or in any particular order regarding a specific symmetry. The paintings do not represent material assets, they cannot be taken down and carried away, yet still, they never cease to be in motion. And though the wall is hung with stretcher frames, they don't hold canvasses but are equipped with lacquered surfaces to reflect these animated painterly projections. Their light source is not readily obvious. Does the projection come from behind the translouscent surface? Or do the screens hung on the wall reflect a ray of light?

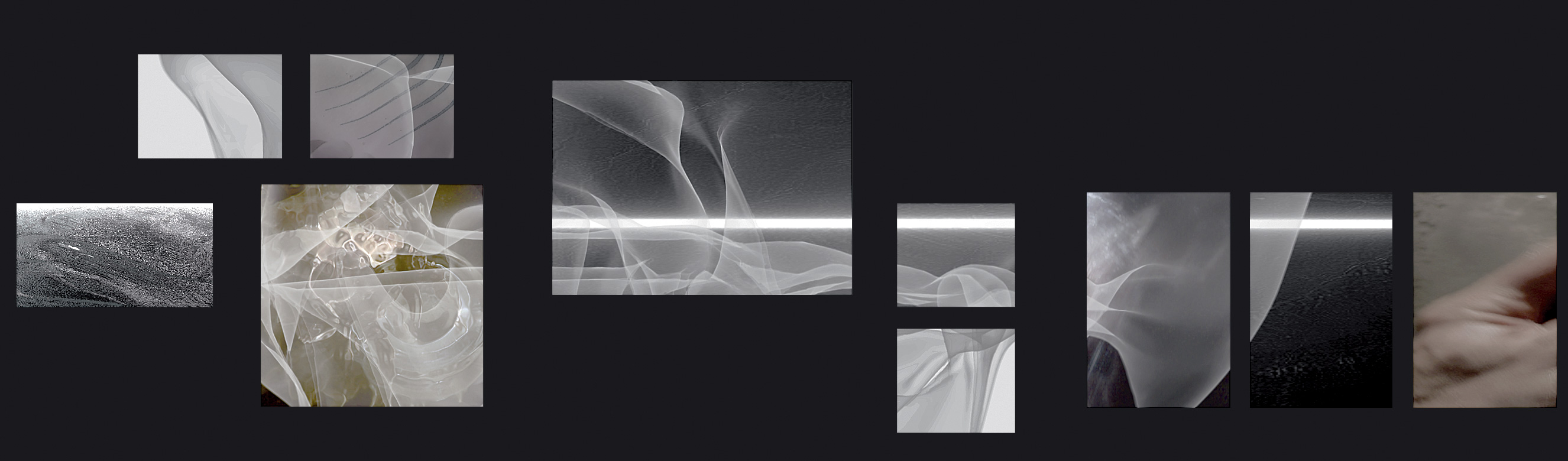

Three video projectors project the ever changing images onto a total of ten screens. These projection surfaces are not framed but elevated from the dark wall. Owing to this subtle effect the images stand out from the wall and from each other while the two dimensional projections create a virtual image space and at the same time the effect of a real depth of space.

It is not a pure or "naked" sense of vision, that the artist is concerned with. The title of her work – naked eye –is therefore less a promise than an ironic hint to what is not shown, however visible or not. The window panes for instance which in the installation refer to the difference of exterior and interior in the truest sense of the word, show a sentence by Alfred Adler. As the founder of individual psychology, about the complexity of communicative processes. In just a few words Adler postulates the analytical distance which can only arise, provided the ambiguities of self expression do not go unnoticed, when new contexts and reference systems are brought into the game; i.e. when seemingly by chance expressions are perceived and can be read and recognised as meaningful gestures: "If what the patient says seems ambiguous and confusing, close your ears and open your eyes wide. Watch him closely when he talks and you will understand exactly what he does not tell you."

The installation refers to the visible context of the exhibition room, primarily however, it addresses the social frameworks we are never allowed to see with the "naked eye" when looking at an aesthetic object. So, art too is under observation like a patient and its viewers are aware and put in a position which should allow for reflection.

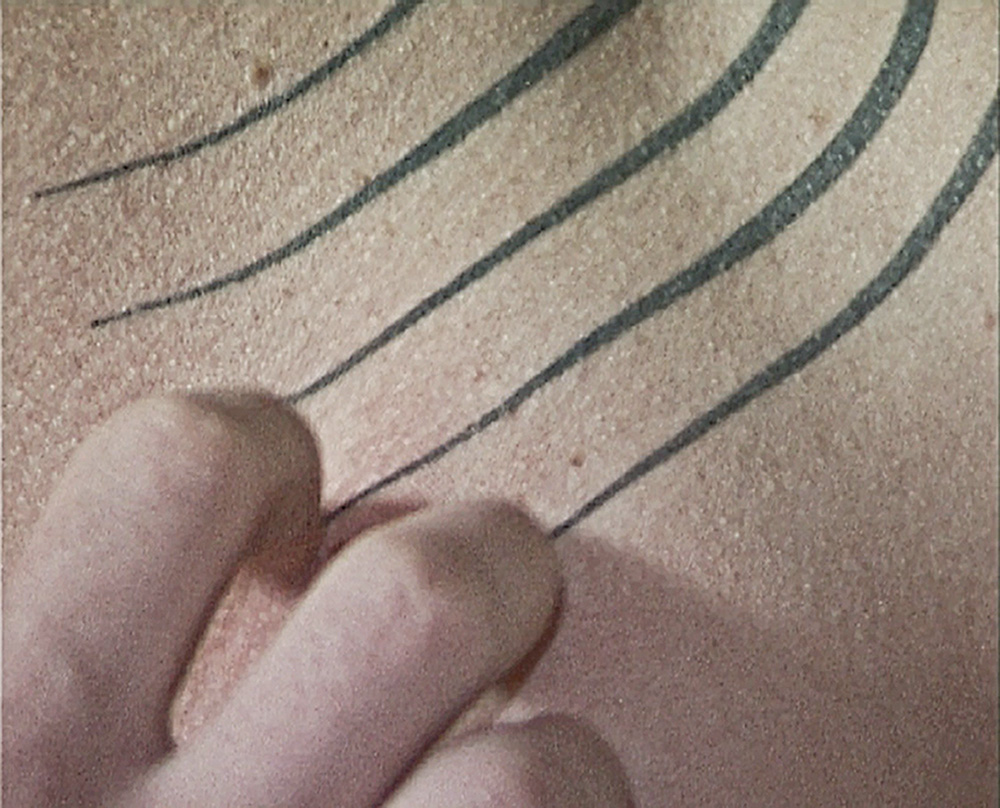

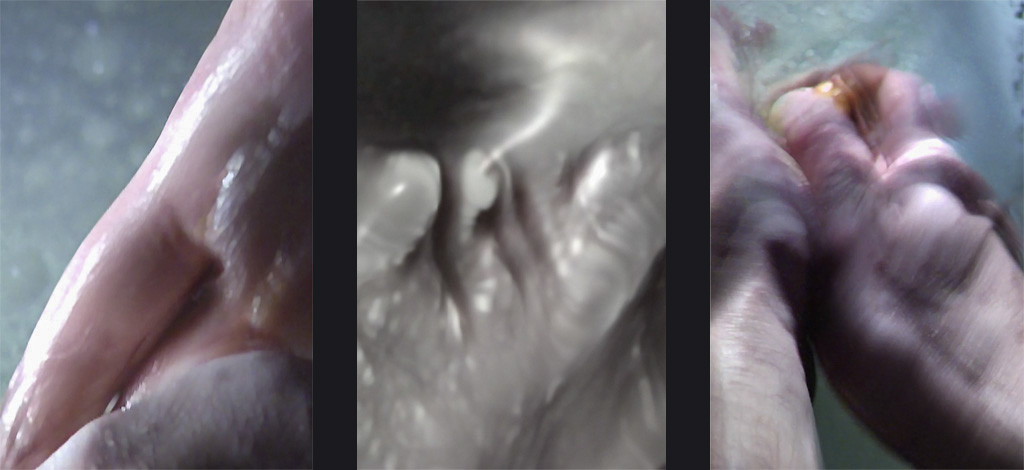

Both in and with her installation, Sylvia Eckermann confronts the observer with inconsistencies that trigger a highly productive state of confusion. From close up these perceived panel paintings quickly (albeit not immediately) turn out to display projections, cinematic images – human skin for instance being scratched or actually drawn upon by fingernails. We see landscapes or abstract figures set into motion, their fine lines allowing for three dimensional effects by means of rotation, simultaneous shading and super-in-position. A triptych continuously releases ever new parts of an endless body landscape. The images thereby transgress their boundaries; their content is no longer restrained to one single area but moves on to go beyond the frame and opens up a second reality which seems to hide underneath or behind them, as flux. As a media installation Eckermann refers to the illusionist techniques of the framed panel as a "built in perspective", yet the contents of her images are applied two-dimensionally; they pay no heed to framing but move on and beyond the frame into another context. It is this contradiction which allows the artist to produce not only an image that appears almost familiar but also to contextualise it with the space, without however forcing the viewer to take a position in an illusionary space. Rather, in Sylvia Eckermann's multimedia installation the space, the image and the gallery merge into one.

This presentation of the images changes the perception of the entire room. By means of sound, colouring and spatial interventions, the exhibition room is withdrawn from our conscious perception. We perceive a mysterious depth in the real room – behind this image wall. The dark walls retreat behind the bright image panes. At the same time the sound does not just reproduce the rhythm of the images, their sequence or filmic movement. It is not just a soundtrack but becomes a separate, independent element: the resonance of which further adds to the sensation that the spatial realities are not what they seem.

As an installation the artist also created a context which enabled her to showcase an ideology of "context-independent art" as represented by the conventional form of the "white cube". In her work Eckermann reflects on the conditions under which aesthetic objects are traditionally received. Instead of creating spatial work, this installation creates space for the disciplines of film and sound. She is not concerned with a contemplative viewing of an individual aesthetic object, but gives the viewer the opportunity to immerse themselves in a "total image" (Oliver Grau). In a panorama of moving pictures, of sound coming from an imagined nothingness, the moving pictures irrigate the perception of a seemingly pictured wall. We do not see unalterable situations nor do we follow any compelling narration. This built space of the imagination is not experienced collectively but by the individual.

Sylvia Eckermann catches her audience at well rehearsed and established reception practices, she dissects traditional forms of image presentation – both static and moving – and subverts the familiar viewing of art. In the end she seduces her audience with an intensive viewing of cinematic material which in this particular case is presented with sophisticated irony and includes technologically defined aesthetic experiences.

This exhibition does not show panel paintings but intangible, even placeless objects – objects that can't be easily allocated and thus manage to call for the undivided attention of each and every one.

Brigitte Felderer, Curator and cultural scientist She teaches at the University of Applied Arts in Vienna The article appeared in: fair • Zeitung für Kunst und Ästhetik – Wien / Berlin. Translated by Jacqueline Csuss